I know some people have a hard time answering the question “what’s your favorite place you’ve ever been?” Not me. Hands down, it’s Glacier National Park and the Canadian Rockies (and yes, I know those are technically two separate places).

In fact, I love Glacier so much that we originally planned to get married there. It didn’t end up happening (you can read about that drama here) but honestly, it was for the best because our actual wedding was everything we wanted it to be. And instead, we were able to spend twelve days in the park this summer to celebrate our first anniversary. It was an amazing trip and I have so much to share, so get ready to listen to me talk about Glacier for the next… well, for a while.

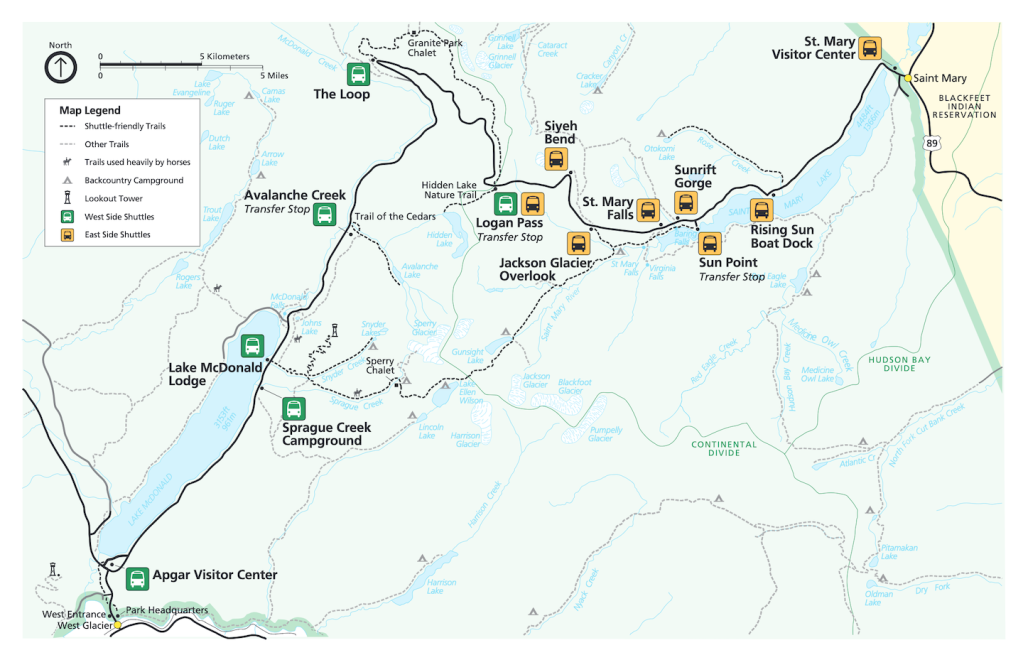

I figured it would be good to start with just an overview of the park itself, because there aren’t a lot of roads and you can’t easily drive from one place to another. Also, everyone else has apparently figured out how amazing Glacier is and it’s become very crowded. In an attempt to mitigate the parking nightmares and destruction of this beautiful wilderness, the park has implemented various visitation control measures. They work, to some extent at least, but they can also be challenging to navigate if you aren’t familiar with the system. Hopefully, this post will help.

- Park history

- Entering the park

- Where to stay

- Getting around

- Going-to-the-Sun Road

- Many Glacier

- Two Medicine

- Cut Bank

- North Fork

- Belly River

- Goat Haunt

- Staying safe in Glacier

- Hiking in Glacier

- Weather in Glacier

- Visiting Glacier

But first, a brief history

Glacier was established as a national park in 1910, but prior to this it was the home of the Aamsskáápipikani (Blackfeet), Séliš (Salish), Ktunaxa (Kootenai), and Ql̓ispé (Pend d’Oreille) people for thousands of years. While the Blackfeet Reservation is now located immediately adjacent to the park’s eastern boundary – you’ll drive through their land as you approach from the east, so please respect their laws, traditions, and culture – the other tribes have been completely displaced and now live on reservations in different states. Programs such as Native America Speaks have been established to educate park visitors on the indigenous history of this land, and you will notice some features in the park retain their indigenous names as well (though, over the years, some of these names have been mistranslated or changed).

Taking a few steps further back in time allows us to understand how this beautiful landscape came to be. The mountains of Glacier were created roughly 170 million years ago by the Lewis Overthrust, an enormous fault that formed when tectonic activity forced a layer of older rock (dated to approximately 1.4 billion years) eastward, pushing it up and over layers of much younger rock. This uplift became the Lewis and Livingston ranges, which run roughly north-south through the eastern and western sections of the park, respectively. Subsequently, the land was covered by glaciers, which carved out bathtub-shaped valleys as they advanced and eventually receded. In fact, Glacier National Park is not named for its current glaciers, but rather for how the landscape was formed. Nonetheless, the 26 glaciers that remain in the park today are a main attraction for those who visit.

The Great Northern Railroad was instrumental in the fight to establish Glacier as a national park, not because they were concerned with conservation but because they saw this glacially-carved landscape as a business opportunity. As soon as the park was designated, the railroad began construction of a collection of Swiss Alps-inspired hotels and chalets and advertised the park as “America’s Switzerland” as part of its “See America First” campaign. Thousands of tourists flocked to the park by rail, then traveled through the park on horseback from chalet to chalet.

The rise of the individually-owned automobile eventually led to a loss of profitability for the rail industry, and many of these hotels and chalets were ultimately torn down. However, today you can still take Amtrak to the park and a handful of the historic buildings still stand. In fact, we stayed at three of them on our trip!

Entering the park

First thing to know: to enter the park you must pay admission ($35/car for a 7-day pass) or present an America the Beautiful pass. If visiting during peak season and planning to enter the park between 6:00am-3:00pm, you may also need a vehicle reservation. These must be purchased in advance; they cannot be obtained at the entrance stations. Visit the website or app for information on availability and how to make a reservation.

Some of the vehicle reservations are released 120 days in advance, while others are held back and released the day before your desired entry at 7:00pm. We were able to obtain a reservation the day before (don’t wait too long, they sell out fast!). Do note, though, that you’ll need wifi or phone service to access the website/app, and both of these are not available everywhere in the park. However, you should be able to find phone service just outside the park, and a couple of the visitor centers have free wifi.

There are separate vehicle reservations for each area of the park, and they are specific to that area only. If you have a lodging or service reservation in the park (camping or hotel reservation, boat tour ticket, horseback ride, etc.), that counts as your vehicle reservation for that specific section of the park during those dates.

Where to stay

Speaking of lodging and service reservations, it’s best to book in advance. Lodging within the park is limited and fills up quickly. I had so much trouble getting us a campsite. I was on the reservation portal the morning they were released, and the available sites were gone in two seconds. Two seconds. That’s not an exaggeration. I literally could not have clicked the “reserve” button any faster, and I still didn’t get a site. It’s become frustratingly impossible.

It all worked out in the end – we found a site just outside the park, and managed to snag some hotel and boat tour reservations closer to the time of our trip – but the whole planning process was stressful. I expect the park will tweak the reservation system for next summer to address some of the issues they’ve faced this season. For now, just know that you have to either be very prompt or willing to wing it at the last minute.

Getting around

While the mileages between destinations in Glacier are not very large, travel times are much longer than you would expect. The roads are narrow and winding, and speed limits are slow. Long story short, plan more time than you think you’ll need to get from point A to point B. Driving across the park from east to west will take a minimum of 2-3 hours, while driving around the park from one entrance to another will require anywhere between 1-3 hours, depending on your starting and ending destinations.

To reduce time spent driving back and forth, you may find it easier to book lodging on the east side of the park for a few days and then switch to west side lodging for the other half of your trip. I personally think the east side of the park is the better half and would plan to spend most of my trip there, but plenty of people are die-hard west-siders.

Going-to-the-Sun Road

By far, the most popular part of Glacier is the Going-to-the-Sun Road (GTSR) corridor, which is the only road that runs all the way through the park from east to west. The west entrance to GTSR is called Apgar and the east is St. Mary. The high point of the road – where it crosses the Continental Divide – is Logan Pass. This is a must-see for anyone visiting the park, and if you only have one day in Glacier, driving GTSR would be my #1 recommendation!

For the best experience in this section of the park, you’ll want to plan ahead and prepare. First order of business is to check the road status. Roads in Glacier aren’t plowed in the winter, and between snowfall and wind, as much as 80 feet (25 m) of snow accumulates! Beginning in April or May, crews use construction equipment to start clearing the roads, but it typically takes until at least mid-June before GTSR is fully open. In particularly snowy years, it may take until July. Therefore, during May and much of June, you won’t actually be able to drive all the way across the park. If you want to see both east and west, you’ll have to go out and around.

Second order of business, if you plan to enter from the west side of the park, is to obtain a GTSR vehicle reservation. Reservations are required from approximately Memorial Day through Labor Day and are good for 1 day only. If you aren’t able to obtain one, you can either enter from the west side before 6:00am or after 3:00pm, catch the free park shuttle from Apgar, or enter from the east side, which does not require vehicle reservations.

The next thing to prepare for is the drive itself. GTSR is a narrow, winding two-lane road that’s been blasted into the sheer, rocky slopes of the mountains. Large vehicles – those over 10 feet (3 m) tall or 21 feet (6.5 m) long – are not allowed, as they will be unable to navigate the tight curves and low-clearance tunnels. The road has no shoulder, and you’ll spend much of the drive with steep drop-offs on one side and cliffs rising above you on the other. If you’re afraid of heights and/or exposure, this may not be the drive for you.

Due to the terrain along GTSR, parking space is limited. The lot at Logan Pass fills before 7:00am daily, leading to parking delays the rest of the day (keep in mind that your GTSR vehicle reservation doesn’t guarantee parking, only that you will be allowed to enter the corridor during that timeframe).

My recommendation is to take advantage of the free park shuttles rather than driving the road yourself. It’s admittedly not the most convenient – you have to transfer a couple times and you may have to wait a few minutes if a shuttle is full – but I find it to be so much less stressful. Plus, you don’t have to worry about parking, and you can enjoy the view without accidentally driving into a cliff… or off the road. While the shuttles don’t stop at every parking lot or viewpoint, you can reach most everywhere along the GTSR corridor this way.

Multiple posts about hikes and other highlights of the GTSR corridor will be published in the coming weeks.

Many Glacier

Many Glacier is the northeast section of the park and the one with – you guessed it – many glaciers. (Though, sadly, climate scientists anticipate all of Glacier’s glaciers will have vanished by 2030.) This is also the area in which I’ve seen the most wildlife – including moose and bears – and hiked the most miles. It’s my favorite area of the park and will feature heavily in upcoming posts.

The road into Many Glacier does not connect to any other roads in the park, so to reach this section from elsewhere you will need to exit the park and drive north to the tiny town (if you can even call it that) of Babb. From here, a partially-paved, partially-dirt road parallels Lake Sherburne and enters the park. From approximately July 1-Labor Day, you will need a vehicle reservation to enter Many Glacier between 6:00am-3:00pm. Reservations are good for 1 day only. As with other areas of the park, you can enter before or after that window with no reservation.

Despite its incredible beauty, this is a rather small area. Parking is limited and there are no shuttles, so you’ll want to either book overnight accommodations in Many Glacier or plan to arrive early. We typically arrived by 8:00am and had no trouble finding parking, but the lots did fill by mid-morning.

Also, note that while there are a couple lakes and waterfalls that can be reached via relatively short hikes, most of the trails here – including the one to Grinnell Glacier, which is the most accessible glacier in the park – require quite a few miles and a decent amount of elevation gain. If you’re planning to hike here, be sure to come prepared with food, water, rain gear, layers, and bear spray. I’ll talk more below about hiking and bear safety.

Two Medicine

The southeast entrance to Glacier is called Two Medicine, and it is slightly less popular than the previous two areas but will still fill to capacity by mid-morning. As with Many Glacier, the road into Two Medicine does not connect with any other roads in the park; you’ll need to drive out and around. Also, if you’re accessing Two Medicine from the north – for example, from St. Mary or Many Glacier – you’ll find yourself driving a short stretch of narrow winding road with sheer drop-offs on one side and lots of crumbling asphalt. Basically, be prepared to drive slowly through here.

Don’t let the state of the road deter you, though. The Two Medicine area has a lot to offer, ranging from a beautiful picnic area on the lake shore to scenic boat tours to all-day hikes. In 2024, vehicle reservations are not required to visit Two Medicine.

I visited Two Medicine twice this summer – once with my mom and once with Pat – so there will be a couple posts about this area.

Cut Bank

The most overlooked entrance point, by far, is Cut Bank, an unassuming gravel road that heads in from the eastern edge of the park to the scenic Cut Bank Valley. It dead-ends at a small, primitive campground. No vehicle reservation is needed to enter, but you also can’t reserve the campsites in advance, so if you want to spend a night here you just have to wing it and hope for the best. To travel beyond this point, you’ll have to hike. I’ve driven into Cut Bank for a picnic lunch, but I haven’t ever hiked here. Hopefully someday.

North Fork

I’ve never been to the northwest corner of Glacier, home to Bowman and Kintla Lakes, among others. From what I’ve read, though, this region used to be a hidden gem but has now been discovered. Despite this, it’s still fairly undeveloped; the roads are unpaved and parking is scarce. You’ll need a separate North Fork vehicle reservation to visit this area between 6:00am-3:00pm from approximately Memorial Day through Labor Day. Reservations are valid for 1 day only.

Belly River

The Belly River area is the other hidden gem. I hear. I’ve never really visited, though I have looked out over the area from above. The Belly River entrance is not so much an entrance as it is a trailhead in the farthest northeast corner of the park, just shy of the Canadian border. Most people who hike in via Belly River have backpacking permits; there is a network of trails in this remote section of the park that can be connected to form various multi-day backpacking loops. Aside from backcountry campsites, there’s a ranger station back there that’s sometimes staffed, and that’s it. If you’re looking to get away from it all and experience wild and rugged Glacier, in a place where humans are definitely outnumbered by grizzly bears, this would be your place. No vehicle reservations are needed.

Goat Haunt

Along with Belly River, Goat Haunt is the most remote and least visited section of the park. Unless you feel like hiking a couple dozen miles, Goat Haunt is best reached by boat. From Canada. Located at the southernmost tip of Upper Waterton Lake, you’ll find a boat dock, a sometimes-occupied ranger station, and presumably some mountain goats. Since the boat departs from Canada and you cross the border while you’re on the water, you’ll need to have a boat ticket and a passport to visit Goat Haunt. It’s a journey I hope to make someday!

Staying safe in Glacier

This is bear country. Glacier is home to relatively large populations of black and grizzly bears, and it’s important to be able to tell them apart in case you encounter one. Which, by the way, is reasonably likely. I don’t think I’ve ever gone to Glacier and not seen multiple bears. Even if you don’t hike, you may still see a bear. They often wander into campgrounds and cross roads, so you should be prepared for a bear sighting no matter where you are. My #1 rule for Glacier is to never go anywhere without a camera, binoculars, and bear spray.

That being said, 99% of bear encounters are peaceful and occur at a safe distance, and I’ve never had a scary one.

(Moose, on the other hand, are a whole different story. Truth be told, I’m far more scared of running into a moose than a bear. It’s not a bad idea to brush up on moose safety, too. But I digress.)

First things first: black bears are not always black. They can range from light brown to dark brown to black. Grizzly bears are not typically black, but they can be any shade of brown as well. In other words, fur color isn’t going to help you identify the bear.

While there are many differences between black and grizzly bears, the one thing that’s always helped me tell them apart is to remember that grizzlies are curvier and black bears are straighter. What does that actually mean? The body of a grizzly is more contoured; they have a hump on their back, a concave or dished face profile, and rounded ears. They also have longer, more curved claws (though if I’m close enough to a bear to see its claws, I don’t think I’m going to be terribly concerned with which type of bear I’m dealing with).

Black bears, on the other hand, have no hump, a flatter face profile, and pointier ears. Here is a website with photos.

Why does this matter? Because if you encounter a bear, you’ll need to know how to behave. No matter what kind of bear it is, the number one goal is to keep your distance – at least 100 yards (91 m), though that can be difficult to estimate. A good test is the rule of thumb: extend your arm, hold up your thumb, and close one eye. If you can block the bear from your view with just your thumb, you’re far enough away. If not, you’re too close.

If you do end up too close to a bear, turn sideways and move away slowly. Don’t make eye contact, but don’t turn your back on the bear either. As you move, talk to the bear – but don’t yell – to help it identify you as human. If you have young children, pick them up or keep them close. Most of the time, once the bear realizes you’re not a threat it will leave you alone and go about its day. It’s a common misconception that bears are naturally aggressive, but the truth is they don’t want to run into you any more than you want to run into them. They’re only aggressive when they feel threatened, which generally only happens when you surprise them or when you end up between a mama and her baby.

To limit the risk of a surprise encounter, it’s best to hike in groups during daylight hours and make plenty of noise. If a bear hears you coming, it will generally move out of the way. Carrying on a conversation, singing, or clapping is sufficient to announce your presence, unless it’s windy or you’re close to rushing water, in which case you might need to periodically let out a loud yell. Be especially sure to make plenty of noise as you approach blind corners or any other terrain where visibility is limited.

(By the way, bear bells don’t count as noise. They’re not nearly loud enough, and really just make you sound like a bird or a rodent or something else that a bear might want to investigate as a potential breakfast option.)

If backing away isn’t enough to appease the bear, this is when it’s important to know which species you’re dealing with. If it’s a black bear and it comes running at you, make yourself large. Put your kid on your shoulders, lift your arms above your head, flail your hiking poles around, yell and scream. If the black bear attacks, fight back however you can. Throw rocks, kick it, poke it, etc.

If it’s a grizzly, don’t do any of these things. Drop to the ground and play dead. Keep your backpack on for protection and lay flat on your stomach with your legs spread wide. Interlace your hands on the back of your neck and brace your elbows on the ground. This position will provide maximum protection to your vital organs while also making it more difficult for the bear to roll you over.

Even better: carry bear spray and know how to use it. It needs to be easily accessible; you should be able to have it deployed within seconds, so practice unclipping it from your pack, removing the safety, and aiming it. It has a range of about 30-60 feet (10-20 m) so you have to wait until the bear is relatively close and you have to spray it at eye level for the bear and account for any wind. Be sure you’re not standing downwind of the spray where it will blow back and incapacitate you rather than the bear.

Here is more information on bear spray, and here is additional information about bear safety and how to handle an encounter.

Hiking in Glacier

There are over 700 miles (1125 km) of trails in Glacier, ranging from short and paved and accessible to steep and rocky and very difficult. Pat and I actually met someone who has hiked every single trail in the park; that’s no easy feat! While that’s not what most visitors set out to accomplish, the point is: there’s something here for everyone. The park website has pages of information and tables and maps of all the trails, and you can also pick up a trail guide at a visitor center or entrance station. This will allow you to identify trails that are best suited to your interests and abilities.

No matter the hike you choose, you’re in a wilderness area with many potential hazards, including rocks and roots on which you might roll an ankle, rapidly-flowing (and cold) water that could sweep you away if you slip and fall in, wild animals, biting insects, and ever-changing weather. You’ll also most likely not have any phone service. I don’t say this to scare you, but rather to emphasize why proper preparation is important for even the shortest of hikes. Always carry bear spray plus the Ten Essentials, and be sure to let someone you trust know where you’re going and when you plan to return.

Lastly, always have a backup plan in mind. If bears are frequenting a specific area, the park will close the trails. I’ve been to Glacier multiple times, and I’ve never not had to change at least one of my planned hikes due to a bear closure.

Weather in Glacier

If I could describe the weather here in one word, it would be ‘unpredictable.’ Even in June, July, August, and September, it could snow, it could rain, it could be foggy, or it could be warm and intensely sunny. You might experience all of the above in the same day. It’s not entirely uncommon to go from sunglasses to raincoat and back again in a 15-minute period.

In other words, no matter how short the hike, always bring layers, rain gear, and sun protection.

Visiting Glacier

Last but not least, prepare to have the adventure of a lifetime. Glacier is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and a World Heritage Site, as well as comprising half of the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park, which was the first in the world of its kind. The park has been dubbed the “Crown of the Continent,” and rightfully so. No matter where you are, you’ll find yourself surrounded by lakes and waterfalls, wildflowers and wildlife, towering mountains that make you feel tiny, and fresh air that makes you feel alive.

I don’t even know if I can find the words to describe how at peace I feel amongst these incredible mountains, and I’m so excited to spend the next few posts sharing our Glacier adventures with you!

Wow! I’m not even sure what to say other than wow! One of my biggest “next time” places (not quite regret, as it was the wrong time of year) after our big American road trip was Glacier National Park. I always said next time we go to Banff, we’d drive down over the border just for Glacier. This has totally convinced me that we need to do it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yay! I hope you’re able to do that because Banff + Glacier would be an amazing trip!

LikeLike

What a great post Diana and it’s nice that you included some safety tips as well. I’ve never been to this part of the world though. We’re thinking maybe next summer but I’m still very intimidated to do the planning. I’m taking some notes though. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I’m glad I could help, and I hope you make it to Glacier. I’m happy to answer any questions you have during the planning process as well 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Diana! I’ll take your offer when the time comes (hopefully next year).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this amazing, exhaustive summary of Glacier NP, Diana. It must have taken you days (weeks?) to perfect. Your love and concern for the park shine through your every word and photo.

I regret that we only drove through the park on our way to Alaska many years back and didn’t have or take the time to explore it, especially since no reservations were required and huge crowds weren’t an issue then. That we are “loving our National Parks to death” remains a true threat and challenge.

LikeLike

If I ever plan to go to Glacier, I will look up this post! Great information. The lakes are so beautiful and that Montana sky!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad I could help! It’s gotten much more complicated to visit the park so hopefully this clarifies some of it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just by looking at your beautiful photos, I can understand why this is (one of your 😉) favourite places. “Going-to-the-Sun Road” – what a lovely name … I want to go there right now (though not in those misty conditions on your photo)! As for the bears – I would love to see one in the wild one day … but preferably from further than 100 yards! And lay on the ground when a grizzly comes running towards me – that will be very hard! I’m looking forward to your next posts about this stunning place!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, I have to imagine I’d be totally panicking if a bear actually came running at me. I have no clue how I would react. Hopefully I never have to find out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post. It’s such a beautiful park!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

A fantastic write-up and guide! And awesome job with the images too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

It’s been many years since I’ve been to Glacier, but even though I’ve been, I’m just a rookie. You are the indisputable expert. What a great and informative read, Diana. Looking forward to reading about your adventures in the bear-free comfort of my home.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re about to be reading about Glacier for the next two months so be careful what you wish for! Haha! But I promise all the bears will be only virtual for you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are an encyclopedia for Glacier National Park! The husband and I have yet to visit, but when we do get around to it, I will definitely reference this post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw this is such an informative post Diana, and the photos are just stunning so I can only imagine how special a place it is in person. I absolutely love your shot of St. Mary Lake 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, Hannah! It’s funny you picked that as your favorite because it’s one of the most photographed locations in Glacier!

LikeLike

A lot great information for Glacier. It hasn’t been that long since we’ve been, but sounds like amount of visitors has greatly increased as with the amount of permits. Are bear bangers allowed in national parks? We always carry those as well as bear spray. Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d never even heard of bear bangers and had to look them up. I don’t think I’ve ever seen or heard one be used. It seems like they’re legal in some places but not others, so I have no idea whether they could be used in Glacier. Do they cause sparks? If they could cause a fire, I imagine they’d be prohibited during fire bans. But I truly have no clue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

They don’t give a spark or they wouldn’t be allowed in Alberta or BC. They just give two loud bangs. We had to use them when we startled a momma bear. We were on bikes so came up to her pretty quick. They worked perfectly so she ran off just far and long enough for us to get out of there on our bikes.

LikeLike

All this talk about Glacier makes me want to return. It’s one of my favourite places as well, along with the Canadian Rockies. How fun to spend your first anniversary there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hopefully you’re able to make it back before too long! If not, you can visit vicariously through me for the next few weeks 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

An extensive and thorough guide to Glacier National Park! It’s unbelievable that places get booked out well in advance, but good that you managed to snag a spot! Looks absolutely worth the trip, and a trip of a lifetime!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really is, I so hope you make it there one day soon!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is an amazing travel guide, and this post definitely makes me want to check out the park!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You definitely should! Thanks for dropping by!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was a fantastic, thoughtful, and very useful guide to this park! Definitely going to save this for future use. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Glad it was helpful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a very detailed post about Glacier National Park, Diana. We were in Glacier back in 2010 when we started visiting the US national parks, and Glacier has been on top of my favorite parks since. I love it so much that in 2020 we even booked an RV camping spot at St. Mary’s, which was hard to get. But we had to cancel our reservation because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Your pictures of Glacier NP and the post remind me to revisit the park one day. I look forward to your other posts of Glacier. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Keng! I hope you make it back soon and you’re able to find a camping spot. Finding accommodations was tricky for us but it all worked out in the end.

LikeLike

Informative post. I wish I would have read this before I went there several years ago!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks!

LikeLike

An awesome post Diana. You seem to have thought of it all. We have been through the GTSR a few times, but other than that not really spent much time in the park. It is as you describe it, drop dead gorgeous, as is our smaller Waterton Lakes portion. Thanks for sharing. Allan

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Allan! I’m excited to show you some other portions of the park through my next few posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such a wonderful guide! I hope I go to Glacier soon and when I do this will be such an incredible resource. I’m pretty sure my parents saw a grizzly bear when they were there and they were terrified.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s awesome that they got to see one though! It’s scary when you don’t know what to expect. Pat was scared too, but then we had a peaceful sighting and he thought it was so cool. Hopefully that was their experience too.

LikeLike

Such a fantastic and valuable post, Diana! One thing, (there are many others, of course), I love about GNP is its pristine waters, including our rivers and lakes, and how clear and clean they are. And I love how, despite its popularity, the park has maintained a sense of solitude. Thanks for sharing, and have a great day 🙂 Aiva xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Aiva! I love the water too, it’s amazing how some of it is crystal clear and some of it is milky turquoise. It’s such a contrast.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s realy a very informative blog for people who want to visit Glacier National Park. It’s a place that would attract me very much. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!!

LikeLike

Wow! That’s a great complete post Diana! Many info, good details and nice photos too!

The Many Glacier Hotel also looks very appealing with the peak on the background.

Thanks for sharing such a great post Diana!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! The Many Glacier Hotel is quite possibly the most beautiful place I’ve ever stayed. If you ever make it to Glacier, I highly recommend the splurge.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many years ago I parked at the visitor centre and hiked on the opposite side of the highway. I don’t recall the distance but the trail led to a lodge in the mountains that is only accessible by hiking in or by horseback. Do you know what the name of the backcountry lodge was and if it is still operating? It certainly was beautiful country. I recall seeing a lot of bears, more than I’ve ever seen anywhere else. However there were a lot of people on the trail and the bears seemed to keep their distance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds like either Granite Park Chalet or Sherry Chalet. They are both still operational, and we actually stayed at Sperry on this trip!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Thanks for such a thorough post Diana. Glacier NP has a lot to offer and you covered it all. It is great that large mammals like grizzlies and moose have returned. I’d love to visit and stay in a chalet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Yes, moose and bears have returned and populations continue to increase. It’s relatively common to see both now when you visit.

LikeLiked by 1 person